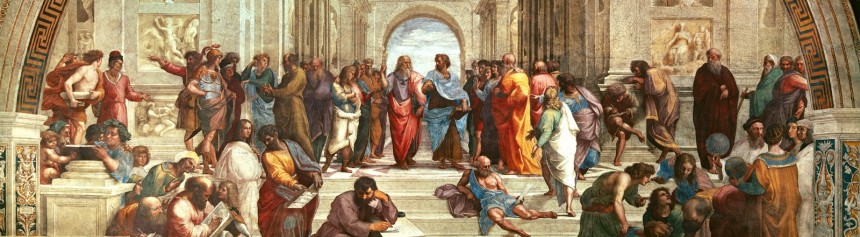

What Is the Value of a Face-to-Face Education on a Liberal Arts Campus?

A research project made possible by a fellowship from

the Wofford College Center for Innovation and Learning

As liberal arts institutions consider offering more education online, it is vitally important that we understand and articulate the advantages of classroom and other in-person interactions for student engagement and learning outcomes so that institutions and students can make informed decisions in choosing online, on-campus, or blended education. The goal of this study is to articulate the unique in-person interactions that enrich learning in a liberal arts environment and to better understand how, when, and where the most effective and engaging interactions happen. To that end, I will employ a qualitative research method that combines direct observations of classroom, lab, and other in-person interactions with interviews of faculty, staff, and students about teaching and learning on a liberal arts campus.

Nature and goals of project

The primary goal of this study is to identify and articulate specific ways in which teaching and learning prosper through in-person interactions on a liberal arts campus. I will share my findings with: (1) Wofford faculty and staff so we can know what we are doing well and do more of it; (2) the board of trustees so that they can better understand how learning happens on our campus and make informed decisions about the growth of our campus or the offering of online content; (3) current and prospective students so they can understand the advantages of studying in-person at Wofford within the liberal arts campus experience; (4) other higher-education professionals so that other similar schools facing the same decisions as Wofford can think about what aspects, if any, of in-person teaching and learning can be preserved or translated in online education.

This study will employ a phenomenological method based on the early-20th-century works of the philosophers Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Phenomenological methods are designed to study experience itself as objectively as possible. In the practice of phenomenology, the researcher classifies, describes, interprets, and analyzes structures of experiences related to a particular phenomenon. [1] In the case of the present study, the phenomenon I will investigate is the lived experience of teaching and learning on a liberal arts campus. The term “lived experience” is often used in phenomenological studies to highlight the underlying assumption that the truths and facets of a phenomenon are best known by those who directly experience them. I will explore this direct experience of the phenomenon of teaching and learning on a liberal arts campus in two ways: by recording my own direct observations of classroom, lab, and other interactions at Wofford and by interviewing Wofford faculty, staff, and students about their lived experiences of teaching and learning on our campus. I will compile the data gathered from this combined method in a way that will preserve the anonymity of those observed and interviewed.

For my observations of classroom and other in-person interactions, the phenomenological method requires that I make myself aware of and then set aside any presuppositions, prejudices, expectations, associations, or assumptions so that I can watch and listen from an objective perspective, looking for details that I might not notice were I in my regular role as a teacher. This kind of observation yields rich and varied details that help highlight previously overlooked aspects of a phenomenon. For the interviews, the method I will use is one I developed in 2005[2] that has since been cited in studies in education, social work, and action research.[3] It combines two kinds of approaches: First, critical incident prompts invite interview participants to recall a time that stands out for them. For instance, I might say to a student, “please think back to a time when you were really engaged while in the classroom,” or to a professor, “tell me about one of your best teaching moments.” These kinds of prompts elicit narratives that vividly illustrate the interview participant’s personal and direct experience with a phenomenon. Second, Socratic-hermeneutic questioning complements these narrative-seeking prompts by engaging the interview participant in back-and-forth dialogue that asks the participant to question and explore his or her own deeply-held beliefs on a phenomenon. Direct observations will be recorded in field notes, and interviews will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to create texts for analysis.

Bibliography

Beard, Lawrence A., Cynthia Harper, and Gena Riley. “Online Versus On-Campus Instruction: Student Attitudes & Perceptions.” TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning 48.6 (2004): 29–31.

Beasley, Nicholas M. “The Liberal Arts at Sewanee: a History of Teaching and Learning at the University of the South.” Anglican and Episcopal History 79.3 (2010): 302–304. Print.

Coates, Hamish. “A Model of Online and General Campus-based Student Engagement.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 32.2 (2007): 121–141.

Dinkins, Christine. “Shared inquiry: Socratic-hermeneutic interviewing and interpreting.” In Beyond Method: Philosophical Conversations in Healthcare Research and Scholarship. Pamela M. Ironside, ed. University of Wisconsin Press, 2005.

Flowerday, Terri and Schraw, Gregory. “Teacher beliefs about instructional choice: A phenomenological study.” Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol. 92(4), Dec 2000, 634-645.

Morrel, Judith, and Michael Zimmerman. “Liberal Arts Matters at Butler University: An Experiment in Institutional Transformation.” Peer Review 10.4 (2008): 12–15.

Pascarella, Ernest. “Effects of an Institution’s Liberal Arts Emphasis and Students’ Liberal Arts Experiences on Intellectual and Personal Development.” ASHE Higher Education Report 31.3 (2005): 59–70.

Pascarella, Ernest. “Impacts of Liberal Arts Colleges and Liberal Arts Education: A Summary.” ASHE Higher Education Report 31.3 (2005): 87–100.

Seifert, Tricia A, Kathleen M Goodman, et al. “The Effects of Liberal Arts Experiences on Liberal Arts Outcomes.” Research in Higher Education 49.2 (2007): 107–125.

Yu, Pauline, and Francis Oakley. “Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities.” ACLS Occasional Paper 59 (2005): v. Print.

[3] See, e.g., Brinkmann, S. “Interviewing and the Production of the Conversational Self.” Qualitative Inquiry and Global Crises (2011): 56; Cole, M. “Hermeneutic Phenomenological Approaches in Environmental Education Research with Children.” Contemporary Approaches to Research in Mathematics, Science, Health and Environmental Education (2010); and Scheckel, M., N. Emery, and C. Nosek. “Addressing Health Literacy: The Experiences of Undergraduate Nursing Students.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 19.5-6 (2010): 794–802.